- Social Conditions in the 18th-century France

- First and Second Estate

- Third Estate

- The Monarchy

- The Intellectual Movement

- Outbreak of the Revolution

- After Fall of Bastille

- War and End of Monarchy

- Napoleonic Wars

- Consequences of the Revolution

- Impact of French Revolution on the World

- Revolutions in Central and South America

The French Revolution was brewing while the War of American Independence was being fought. Conditions in France were vastly different from those in the New World, but many of the same revolutionary ideas were at work. The French Revolution, however, was more world-shaking than the American. It became a widespread upheaval over which no one could remain neutral.

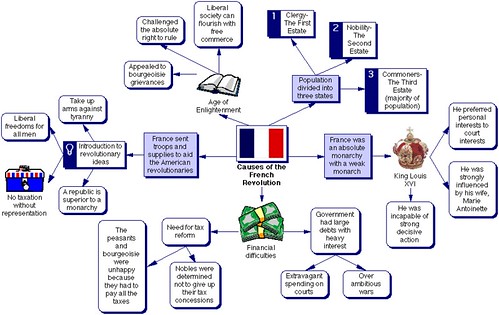

Social Conditions in the 18th-century France

- To understand how and why the French Revolution occurred, we have to understand French society of that time. We have to realize also that conditions in France were no worse than the conditions that existed in other parts of Europe.

- Autocratic, extravagant rulers, privileged nobles and clergy, landless peasants, jobless workers, unequal taxation—the list of hardships endured by the common people is a very long one.

- France was a strong and powerful state in the 18th century. She had seized vast territories in North America, islands in the West Indies. However, despite its outward strength, the French monarchy was facing a crisis which was to lead to its destruction.

First and Second Estate

French society was divided into classes, or estates. There were two privileged classes

| Privileged class | Also known as | Population |

| Clergy | First estate | 1.3 lakh clerics |

| Nobility | Second estate | 80 thousand families |

- People in these two classes were exempted from almost all taxes!

- They controlled most of the administrative posts and all the high-ranking posts in the army.

- In a population of 25,000,000 people, these two classes together owned about 40 per cent of the total land of France. Their incomes came primarily from their, large land-holdings.

- A minority of these also depended on pensions and gifts from the king. They considered it beneath their dignity to trade or to be engaged in manufacture or to do any work.

- The life of the nobility was everywhere characterized by extravagance and luxury. There were, of course, poorer sections in these two top estates. They were discontented and blamed the richer members of their class for their misery.

Third Estate

The rest of the people of France were called the Third Estate. They were the common people and numbered about 95 per cent of the total population. People of the Third Estate were the unprivileged people. However, there were many differences in their wealth and style of living.

The Peasants

- The largest section of ‘the Third Estate consisted of the peasants, almost 80 per cent of the total population of France. The lives of this vast class were wretched. Most of the peasants were free, unlike the serfs in the Middle Ages, and unlike the serfs in eastern Europe in the 18th century. Many owned their own lands. But a great majority of the French peasants were landless or had very small holdings.

- They could earn hardly enough for subsistence. The plight of the tenants and share-croppers was worse. After rents, the peasant’s share was reduced to one-third or one-fourth of what he produced. The people who worked on land for wages lived on even less.

- Certain changes in agriculture in the 18th century France further worsened the condition of the peasant. He could no longer take wood from the forests or graze’ his flocks on uncultivated land. The burden of taxation was intolerable. Besides taxes, there was also ‘forced labour’ which had been a feudal privilege of the lord and which was more and more resorted to for public works. There were taxes for local roads and bridges, the church, and other needs of the community. A bad harvest under these conditions inevitably led to starvation and unrest.

The Middle Classes

- Not all the people belonging to the Third Estate worked on the land. There were the artisans, workers and poor people living in towns and cities. Then there was the middle class or the bourgeoisie.

- This class consisted of the educated people— writers, doctors, judges, lawyers, teachers, civil servants— and the richer people who were merchants, bankers, and manufacturers.

- Economically, this class was the most important one. It was the forerunner of the builders of the industries which were to transform economic and social life in the 19th century.

- The merchant-business groups, though new in history, had grown very important and rich, helped by the trade with French colonies in America.

- Since these people had money, the state, the clergy and the nobility were indebted to them. However, the middle class had no political rights. It had no social status, and its members had to suffer many humiliations.

The Artisans and City Workers

- The condition of the city poor—workers and artisans—was inhuman in the 18th-century France. They were looked upon as inferior creatures without any rights.

- No worker could leave his job for another without the employer’s consent and a certificate of good conduct.

- Workers not having a certificate could be arrested. They had to toil for long hours from early morning till late at night.

- They, too, paid heavy taxes. The oppressed workers formed many secret societies and often resorted to strikes and rebellion.

- This group was to become the mainstay of the French Revolution, and the city of Paris with a population of more than 500,000 was to play an important part in it. In this number was an army of rebels, waiting for an opportunity to strike at the old order.

The Monarchy

- At the head of the French state stood the king, an absolute monarch. Louis XVI was the king of France when the revolution broke out.

- He was a man of mediocre intelligence, obstinate and indifferent to the work of the government. Brain work, it is said, depressed him.

- His beautiful but ’empty-headed’ wife, Marie Antoinette, squandered money on festivities and interfered in state appointments in order to promote her favorites. Louis, too, showered favours and pensions upon his friends.

- The state was always faced by financial troubles as one would expect. Keeping huge armies and waging wars made matters worse. Finally, it brought the state to bankruptcy.

The Intellectual Movement

Discontent or even wretchedness is not enough to make a successful revolution. Someone must help the discontented to focus on an ‘enemy’ and provide ideals to fight for. In other words, revolutionary thinking and ideas must precede revolutionary action. France in the 18th century had many revolutionary thinkers. Without the ideas spread by these philosophers, the French Revolution would simply have been an outbreak of violence.

Rationalism: the Age of Reason

- Because of the ideas expressed by the French intellectuals, the 18th century has been called the Age of Reason. Christianity had taught that man was born to suffer.

- The French revolutionary philosophers asserted that man was born to be happy. They believed that man can attain happiness if reason is allowed to destroy prejudice and reform man’s institutions.

- They either denied the existence of God or ignored Him. In place of God they asserted the doctrine of ‘Nature’ and the need to understand its laws.

- They urged faith in reason. The power of reason alone, they said, was sufficient to build a perfect society.

Attack on the Clergy

- The clergy were the first to feel the brunt of the French philosophers. A long series of scientific advances dating from the Renaissance helped in their campaign against the clergy.

- Voltaire, one of the most famous French writers of the time, though not an atheist, believed all religions absurd and contrary to reason.

- After Voltaire, other philosophers, atheists and materialists, gained popularity. They believed that man’s destiny lay in this world rather than in heaven.

- Writings attacking religion fed the fires of revolution because the Church gave support to autocratic monarchy and the old order.

Physiocrates and Laissez Faire

- The French economists of the time were called ‘physiocrats’. They believed in “Laissez faire” about which you’ve already read in chapter7 (click me)

- According to this theory, a person must be left free to manage and dispose of his property in the way he thinks best. Like the English and American revolutionaries before them, the physiocrats said that taxes should be imposed only with the consent of those on whom they were levied. These ideas were a direct denial of the privileges and feudal rights that protected the upper classes.

Democracy: Jean Jacques Rousseau

- The philosopher-writer, Montesquieu, thought about the kind of government that is best suited to man and outlined the principles of constitutional monarchy.

- However, it was Jean Jacques Rousseau who asserted the doctrine of popular sovereignty and democracy. He said, ‘Man is born free, yet everywhere he is in chains.’ He talked of the ‘state of nature’ when man was free, and said that freedom was lost following the emergence of property.

- He recognized property in modern societies as a ‘necessary evil’.

- What was needed, said Rousseau, was a new ‘social contract’ to guarantee the freedom, equality and happiness which man had enjoyed in the state of nature.

- Rousseau’s theories also contained a principle that had been written into the American Declaration of Independence: no political system can maintain itself without the consent of the governed.

Outbreak of the Revolution

- In 1789, Louis XVI’s need for money compelled him to agree to a meeting of the States General— the old feudal assembly. Louis wanted to obtain its consent for new loans and taxes. All three Estates were represented in it but each one held a separate meeting.

- On 17 June 1789, members of the Third Estate, claiming to represent 96 per cent of the nation’s population, declared themselves the National Assembly.

- On 20 June, they found their meeting-hall occupied by royal guards but, determined to meet, they moved to the nearby royal tennis court to work out a constitution.

- Louis then made preparations to break up the Assembly. Troops were called: rumours spread that leading members of the Assembly would soon be arrested. This enraged the people, who began to gather in their thousands.

- They were soon joined by the guards. They surrounded the Bastille, a state prison,

- On 14 July. After a four-hour siege, they broke open the doors, freeing all the prisoners. The fall of the Bastille symbolized the fall of autocracy. July 14 is celebrated every year as a national holiday in France.

After Fall of Bastille

- After 14 July 1789, Louis XVI was king only in name. The National Assembly began to enact laws.

- Following the fall of the Bastille, the revolt spread to other towns and cities and finally into the countryside. The National Assembly adopted the famous Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. It specified the equality of all men before the law, eligibility of all citizens for all pubic offices, freedom from arrest or punishment without proven cause, freedom of speech and freedom of the press.

- Most important of all, to the middle class, it required equitable distribution of the burdens of taxation and rights of private property.

- The revolutionary importance of this declaration for Europe cannot be overestimated. Every government in Europe was based on privilege. If these ideas were applied, the entire old order of Europe would be destroyed.

War and End of Monarchy

- The people of France were soon involved in a war to defend the Revolution and the nation. Many nobles and clerics fled the country and encouraged foreign governments to intervene in France against the Revolution. The king and queen tried to escape from France in disguise but they were recognized and brought back as captives and traitors.

- The old National Assembly was replaced by a Legislative Assembly. This Assembly took over the property of those people who had fled. It sent word to the Austrian emperor, who was mobilizing support against France to renounce every treaty directed against the French nation. When the emperor refused, the Legislative Assembly declared war.

- Soon France was fighting Austria, Prussia, and Savoy in Italy. The three were supported by an army of the French exiles.

- France had destroyed feudalism and monarchy and founded new institutions based on liberty and equality, whereas in these countries the old way of life remained. The commander-in-chief of the Austro-Prussian forces stated that the aim was to suppress anarchy in France and to restore the king’s authority. The French revolutionaries replied by offering ‘fraternity and assistance’ to all people wishing to destroy the old order in their countries.

- The king and queen were tried and executed in 1793. This was followed by a declaration of war against Britain, Holland, Spain and Hungary.

- Then, a radical group, the Jacobins, believing in direct democracy, tame to power. Fearing that the Revolution was in danger, this group took to strong measures to crush forces inimical to the Revolution. In 14 months, some 17,000 people, including those who were innocent, were tried and executed. Some people have called it the “Reign of Terror“. Later, a new constitution was drawn up. But the army became increasingly powerful and this led to the rise of Napoleon, who was soon to declare himself Emperor of the French Republic.

Napoleonic Wars

- From 1792 to 1815, France was engaged in war almost continuously. It was a war between France and other states. Some historians have termed it as an international civil war because it was fought between revolutionary France and countries upholding the old order. In this war, France was alone.

- However, until Napoleon became emperor, almost every enlightened person in the world sympathized with the French Revolution.

- Between 1793 and 1796 French armies conquered almost all of western Europe. When Napoleon pressed on to Malta, Egypt and Syria (1797-99), the French were ousted from Italy.

- After Napoleon seized power, France recovered the territories she had lost and defeated Austria in 1805, Prussia in 1806, and Russia in 1807. On the sea the French could not score against the stronger British navy.

- Finally, an alliance of almost all Europe defeated France at Leipzig in 1813. These allied forces later occupied Paris, and Napoleon was defeated. His attempt at recovery was foiled at the battle of Waterloo in June 1815. The peace settlement, which involved all Europe, took place at the Congress of Vienna.

- After the defeat of Napoleon, the old ruling dynasty of France was restored to power.

- However, within a few years, in 1830, there was another outbreak of revolution.

- In 1848, the monarchy was again overthrown though it soon reappeared.

- Finally, in 1871, the Republic was again proclaimed.

Consequences of the Revolution

- A major result of the Revolution was the destruction of feudalism in France. All the laws of the old feudal regime were annulled. Church lands and lands held in common by the community were bought by the middle classes. The lands of nobles were confiscated. Privileged classes were abolished.

- After Napoleon seized power. The Napoleonic Code was introduced. Many elements of this Code remained in force for a long time; some of them exist even to this day.

- Another lasting result of the Revolution in France was the building up of a new economic system in place of the feudal system which had been overthrown. This system was capitalism about which you have read in Chapter 7. Even the restored monarchy could not bring back the feudal system or destroy the new economic institutions that had come into being.

- The French Revolution gave the term ‘nation’ its modern meaning. A nation is not the territory that the people belonging to it inhabit but the people themselves. France was not merely the territories known as France but the ‘French people’.

- From this followed the idea of sovereignty, that a nation recognizes no law or authority above its own. And if a nation is sovereign, that means the people constituting the nation are the source of all power and authority. There cannot be any rulers above the people, only a republic in which the government derives its authority from the people and is answerable to the people. It is interesting to remember that when Napoleon became emperor he called himself the ‘Emperor of the French Republic’. Such was the strength of the idea of people’s sovereignty.

- It was this idea of the people being the sovereign that gave France her military strength. The entire nation was united behind the army which consisted of revolutionary citizens. In a war in which almost all of Europe was ranged against France, she would have had no chance with just a mercenary army.

- Under the Jacobin constitution, all people were given the right to vote and the right of insurrection. The constitution stated that the government must provide the people with work or livelihood. The happiness of all was proclaimed as the aim of government. Though it was never really put into effect, it was the first genuinely democratic constitution in history.

- The government abolished slavery in the French colonies.

- Napoleon’s rise to power was a step backward. However, though he destroyed the Republic and established an empire, the idea of the republic could not be destroyed.

- The Revolution had come about with the support and blood of common people— the city poor and the peasants. In 1792, for the first time in history, workers, peasants and other non-propertied classes were given equal political rights.

- Although the right to vote and elect representatives did not solve the problems of the common people. The peasants got their lands. But to the workers and artisans— the people who were the backbone of the revolutionary movement—the Revolution did not bring real equality. To them, real equality could come only with economic equality.

- France soon became one of the first countries where the ideas of social equality, of socialism, gave rise to a new kind of political movement.

Impact of French Revolution on the World

- The French Revolution had been a world-shaking event. For years to come its direct influence was felt in many parts of the world. It inspired revolutionary movements in almost every country of Europe and in South and Central America.

- For a long time the French Revolution became the classic example of a revolution which people of many nations tried to emulate.

- The impact of the French Revolution can be summed up, in the words of T. Kolokotrones, one of the revolutionary fighters in the Greek war of independence: “According to my judgment, the French Revolution and the doings of Napoleon opened the eyes of the world. The nations knew nothing before, and the people thought that kings were gods upon the earth and that they were bound to say that whatever they did was well done. Through this present change it is more difficult to rule the people.”

- Even though the old ruling dynasty of France had been restored to power in 1815, and the autocratic governments of Europe found themselves safe for the time being, the rulers found it increasingly difficult to rule the people.

- Some of the changes that took place in many parts of Europe and the Americas in the early 19th century were the immediate, direct consequences of the Revolution and the Napoleonic wars.

- The wars in which France was engaged with other European powers had resulted in the French occupation of vast areas of Europe for some time.

- The French soldiers, wherever they went, carried with them ideas of liberty and equality shaking the old feudal order. They destroyed serfdom in areas which came under their occupation and modernized the systems of administration.

- Under Napoleon, the French had become conquerors instead of liberators. The countries which organized popular resistance against the French occupation carried out reforms in their social and political system. The leading powers of Europe did not succeed in restoring the old order either in France or in the countries that the Revolution had reached.

- The political and social systems of the 18th century had received a heavy blow. They were soon to die in most of Europe under the impact of the revolutionary movements that sprang up everywhere in Europe.

Revolutions in Central and South America

- The impact of the Revolution was felt on the far away American continent. Revolutionary France had abolished slavery in her colonies. The former French colony of Haiti became a republic. This was the first republic established by the black people, formerly slaves, in the Americas.

- Inspired by this example, revolutionary movements arose in the Americas to overthrow foreign rule, to abolish slavery and to establish independent republics.

- The chief European imperialist powers in Central and South America were Spain and Portugal. Spain had been occupied by France, and Portugal was involved in a conflict with France.

- During the early 19th century, these two imperialist countries were cut off from their colonies, with the result that most of the Portuguese and Spanish colonies in Central and South America became independent.

- The movements for independence in these countries had earlier been inspired by the successful War of American Independence. The French Revolution ensured their success.

- By the third decade of the 19th century, almost entire Central and South America had been liberated from the Spanish and the Portuguese rule and a number of independent republics were established. In these republics slavery was abolished.

- It, however, persisted in the United States for a few more decades where it was finally abolished following the Civil War about which you have read before in this chapter. Simon Bolivar, Bernardo O’Higgins and San Martin were the great leaders in South America at this time.

In the Next parts, we’ll see

- Unification of Germany and Italy; Revolutionary movements in other parts of Europe

- Rise of Socialism

For archive of all World history related articles visit Mrunal.org/history

![[Art Culture] Ancient-Texts: Purana, Mahapuranas, Upapuranas, Characteristics](https://mrunal.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/CleanShot-2022-12-29-at-09.47.10-500x383.jpg)

![[Model Answer] GSM1-2017/Q4: World History- Decolonization problems in Malay Peninsula](https://mrunal.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/c-aoaw-danny-gama-maatin-500x383.jpg)

![[Answerkey] Prelim-2017: History, Culture, Indus Valley Horse, & Science-Technology with explanation for all four sets (A,B,C,D)](https://mrunal.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/c-ana-CSAT17-diwaane-500x383.jpg)

Nice work sir…thanks alot if pissible plz upload book also

Yes

sir after the french revolution a convention was established called convention of vienna to keep a check on France! can u provide me the details abt it sir??

As far as i Remember, Convention of Vienna is after nepolenic wars to nullify his achievements and restore Europe to Pre 1799 kingdoms.

boundaries were redrawn and different powers took posession of different places and France was asked to pay compensation..

France was not asked to pay, it formally established the concept of balance of power, the aim was to empower the nearby countries such that one country alone cannot gain dominance on the continent thus the theme was to maintain equaality among the countries in strategic terms lest should one country wage an unanimous war thus bringing doom over the entire continent

lucid n ready…

sir this article was not good.

Linkages were missing

Clarity was compromised

I agree. many events are missing.

its summarised . to keep it short keeping in view the exam point of view . Its a very large topic to cover there are many expects to it that are not relevant .

sir u done a wonderful work…sir plz upload books names for indian national movements…..

sir can you please provide us the strategy for the preparation of ACIO exam 2013. and also can u suggest us the expected essays for this year’s ACIO exam.

Also, sir please provide us the strategy for the preparation of FCI exam 2013

mrunal sir could you please tell which software you have used to create the mindmap? thanks.

Mrunal Sir, i needed the pdf of old ncert books of history from class 8-10 . Please provide me the needed books.

Nice article sir.

Dr frnd if u got old ncert….pls frwrd it

nice job sir ji… now it is easy to understand

It is explained in such a good manner that now I am understanding it and also finding it very interesting.

It is explained in such a good manner that now I am understanding it and also finding it very interesting. Thank you very much, Sir.

History is not boring subject its realy interesting subject

The condition of France was similar to other European countries but the revolution against monarchy started in France-why?

Awesome mrunal sir. Kip it up.

You are our inspiration.

Can somebody tell me more about Reign of Terror . PLZ

Reign of terror in france was the period mostly between 1793 to 1794.It is named so because of the cold blooded abd aggressive nature of the Jacobian ruler Robos pierre.The jacobians came to power after the fall of National convnetion leaders.They were particularly the lower class people in the france social structure who killed all those against the french revolution!

Pros of the reign:- Abolition of slavery,Threw the monarchy.

Cons- supression of women rights and Mass voilence ,bloodshed

Good

Sir aai mujhe ias main math syllabus and recommrnded book

Is it possible to download it in pdf format.